When we talk about Greek translations, I guess the thing that hits you right off the bat is, “Wait a minute! We’re already up to the sixteenth century!” And that’s a part of the problem. The assimilation of all these Greek manuscripts and fragments into a given total Greek text doesn’t start until pretty late. So right away class, know what you’re talking about! Why is this so? Because when the New Testament was written, it wasn’t written as one complete volume and given to the church. You might have gotten Ephesians. And another church over here might have gotten Philippians, because it was written to Philippi. Now it was true it was passed around and copies were made, but that’s how this whole problem developed and we need to understand that. We are at a great advantage to believe that fourteen of these twenty-seven books were written by one man, Paul.

But when you think about it, all these different men writing these books and then trying to assimilate the information and put it into one volume when you don’t have a printing press. You’re hand copying it! Did you know this was so severe that they literally chained and locked up a given book or manuscript to the pulpit? They only used it when they gathered as Christians. Or if you wanted to come in during the week, you could only use that copy. There isn’t any other way to do this at the time of persecution, when they hit the catacombs. And there were ten general persecutions of the Christians. I mean, sometimes these fragments, they ripped off a copy before the book was destroyed. Maybe it was one book, Philippians. They just ripped off a page of it and kept it in their dear possession. And we know in the catacombs that these people who loved the Lord, they actually were memorizing vast portions and then copying it down in the catacombs.

They would say things like, “Does anybody have John 16?”

“Well, let me check my little piece. Well, only the first three verses.”

“Oh, that will be helpful. Does anybody know John 16?”

And somebody will say, “Well, I memorized it.”

That’s actually how it was done! They tell us, now we don’t know this for sure, but there’s a lot of evidence to the fact that some of these catacomb believers actually could reproduce almost the entire New Testament. Isn’t that interesting? In some countries they do that. They definitely did it at the time of the Holocaust, passing little pages of Scripture around and people copying it down. They especially did that with the book of Psalms. What a blessing! You can imagine getting a little Psalm, like twenty-three.

So anyway, all of this has to be assimilated, all these fragments. So, we are moving into modern times—modern in the sense of the sixteenth century. The first Greek translation to be printed in 1514 was called the Complutensian Polyglot. You say, “I prefer just saying King James.” But the most significant work done on this was done by Desiderius Erasmus. You’ve probably heard the name Erasmus. He was Roman Catholic. He was a part of that Reformation time. And his was the first to be published. There were many copies made and he had editions. Well, at least four of them that we know of: in 1519, then again in 1522, then 1527, then 1533. Erasmus’s work was trusted by others. He did a fantastic job assimilating all the manuscripts that he knew, that were available. And by the way, they represented the Byzantine tradition because they were the ones using the Greek Bible; so most of these fragments and books are coming from them.

We have a man named Robert Stephanus. He is very important. In your notes you want to circle A.D. 1550 because that happens to be the Greek text that was used by the King James translators, A.D.1550. You say, “Boy I’d like to see what that’s like!” Great. You can get the Greek computer program of Logos and it has the 1550 on it. You can actually see the Greek text that was behind the King James. They have four different Greek texts on there.

Another key little note in all these notes is the Elsevier Partners. They produced editions in 1624, 1633, 1641. Just circle 1633, that’s when the name Textus Receptus was given to the Greek text. Interesting that it would be done and there was no attack then saying, “Hey you guys, that is not the received text.” There was none of that. That’s only done today, 300 years removed. When it was done, everybody knew that it was the received text. They knew it was the Greek text used in the churches if they did use Greek. All the western churches used Latin. Isn’t that interesting? So in 1633 it wasn’t trying to start anything. But it just put in Latin letters on it Textus Receptus, the received text. Nobody complained. Everybody knew that was true. Today we have a war over that.

Now, can you get a copy of the Textus Receptus? You sure can. As a matter of fact, it’s in that same four Greek pack that I just told you about on the Logos computer program. So, having Windows, we open one window on our screen. We can actually put four. We open one and we’ve got A.D. 1550. We open the other and we’ve got the Textus Receptus. And I have noticed, because I’ve been comparing them over and over again, in every passage I teach on they are almost exactly the same. There’s hardly any change between the two. Well then, we did have a received text. Well then we did have a tradition that people recognized represented the original text. There wasn’t any variation at all. That’s interesting!

Now there are some variant readings—very few between those texts—more so with the texts I’m going to tell you about in just a little while. But a man named Brian Walton put together a collection of these in 1657. He used the text of Stephanus from 1515. But for the first time, he pulled in a text from the Alexandrian school, called Codex Alexandrinus. He also used another text called Codex Bezae. The reason why I put it in there is because it’s the first time we had a mixture of the traditions. Today when you buy a Greek text it shows all of them put together. But that was the first time we started having a mixture.

Now class—codex—it’s time to remind ourselves of that. Codex is really like our books. They are leaves, pages that are on animal skin. It comes from about the fourth century A.D. on and they are sheets that are tied together with leather thongs. So they are book-like. You can flip them. Because we have complete Bibles or almost complete Bibles in codex, they became dominant manuscripts. They also were in what we call uncial letters. Class, what are uncial letters? Capitals. So people felt they were more reliable. They were easier to read. They became very significant.

Now John Mill, I put him on the list because he’s the first editor to collect evidence of the patristic quotations. You see, even back there in the 1600s, they began to ask some serious questions about the text. How do we know the Greek text used by the churches, called the Received Text, how do we know it’s really the original? John Mill said, “Well the way to check it out is by all the quotations that are in the church fathers. He made it his life’s work. We owe a lot to him…all these verses quoted among all the church father’s writings. Church fathers’ writings are so voluminous. We were just looking at a catalog a moment ago and one set has thirty-eight volumes in it. I mean it just goes on and on. He began to assimilate that and we now have catalogued over 86,000 references or verses out of the church leaders. So it helps us to see that original text, especially if the church leaders lived in the first three centuries. That would be very significant before Constantine.

A man named J. A. Bengle, almost a hundred years go by, and he’s the first to classify the manuscript authorities. When we say there are three traditions, he was the first one ever to do it and he put them into two categories. Called them Asian and African, which would be the Egyptian category. The African had the fewest manuscripts, but they were the oldest ones they had. Why is that? Because in Africa, or in Egypt (primarily they were all in Egypt) we have dry arid climate. So papyrus manuscripts and the actual preservation of them, they would last more. Even if they were buried in the sand, they would last more in a dry climate. You put humidity and rain in there and you destroy the manuscript. So that’s why a great deal of them were found in Africa that are old. But in terms of actual numbers, the majority of manuscripts were of course in Asia. And his idea of Asia included the western and the Eastern Church and a majority of them were there by far.

Now a man named J. J. Wetstein. I’m not going to expect you to know these names, except in certain cases and I’ve already noted two of them for you—the 1550 and the 1633 where we got the name Textus Receptus. But this J. J. Wetstein, he put out editions of Textus Receptus in A.D. 1751-52. Here we have for the first time a critical apparatus, a system of cataloguing the manuscripts. Today class, if you get a Majority Greek text, you look at the bottom of each page, all those little footnotes at the bottom, from what’s in the text is what we call a critical apparatus. What it is telling you is the manuscript evidence behind a given reading in the text. It tells you the manuscript evidence. The first guy to put that in the Greek text was J. J. Wetstein, so we put him in the Greek translation hall of fame.

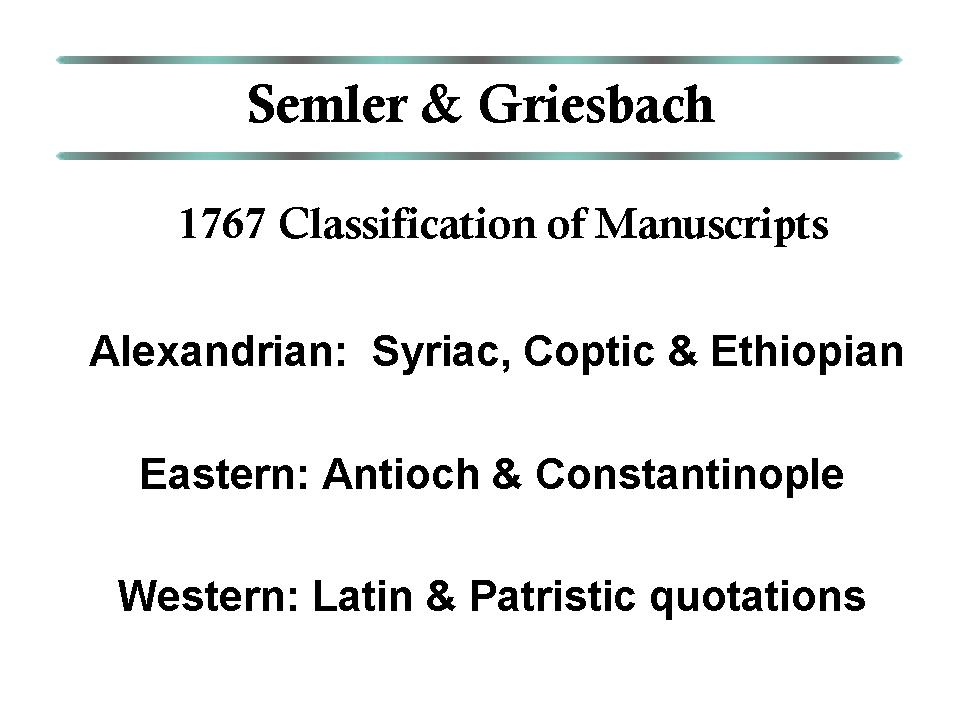

We have actually two men, Semler and Griesbach, who classified the manuscripts into three groups that we still use today. A.D. 1767, so over 200 years ago, we’re still using the same traditions. He pointed out that there are really three traditions and he wasn’t trying to attack Bengle. But thirty years after Bengle he is examining this and saying really what these manuscripts represent are three traditions. We have Alexandrian, which includes Syriac, Coptic, and Ethiopian as well; and the Eastern, which is Antioch, and Constantinople; and the Western, which is Latin and most of the church father quotations. We have not changed from that clear to this day. Those are the three basic geographical traditional areas of manuscript evidence.

Now a name I do want you to know about is Constantine Tischendorf. He’s a German who visited the Saint Catherine’s monastery at Mount Sinai, in the Sinai Desert. And he observed the monks in this monastery burning pages of an ancient book to keep themselves warm. Because he was a scholar dealing with manuscripts of all sorts, not just biblical, he was fascinated. Went over and grabbed a few of them out of their hands and notices they were pages of the Bible. He asked them to stop. Of course he offered them big money and they gave it to him and then burned other books to keep themselves warm. But that hit the world like you cannot believe!

I have seen some newspaper articles, written back at the time of Lincoln even, on this discovery. And it came like a shock through the Christian world. It was a manuscript that had thousands, not hundreds but thousands, of differences from the Received Text that had been used all these centuries. So you see it got everybody stirred up. The other thing is that it was a codex. They were leaves that went together. This manuscript, I won’t tell you the whole history of it, but eventually was bought by the British Museum in London and that’s where you would see it today. I have been there and I have seen it.

The problem is that it would take about 330 leaves to make the whole New Testament. There are only 148 of them. And you know I still read in a lot of books of good men that Codex Sinaiticus was the first completed Bible that was discovered. No, it wasn’t completed at all. I think there are parts from almost every book. But there are a lot of pages missing. Of course, they’d burned a lot. It’s got a lot missing in it. But it had enough, over half of the New Testament, to tell scholars we’ve got to do something about this. This thing has thousands of changes from the Received Text.

It also has some other interesting little things in it. It contains The Epistle of Barnabus. It contains The Shepherd of Hermas, these are apocryphal literature. Totally, they have estimated there are 9,000 changes in that manuscript from the Textus Receptus and they are both in Greek! So can you not see why the scholarship of the world—finding this down in Mount Sinai, the very atmosphere, the very geography of it, that it goes all the way back to the fourth century, one of the earliest manuscripts we’ve ever found almost, the whole Bible is there—can you imagine how the scholars felt? They called it one of the greatest discoveries in manuscript evidence in the history of the world. I think there are parts from almost every book.

Now, the very next thing that happens…Tischendorf found this in 1844, but it took a while for it to, you know, hit the scholastic world and all that. And they are now saying, “Boy we’ve got to re-evaluate what is the original text of the Bible. There was just a massive explosion of scholarship saying, “Wow!”

So, how interesting that the Catholics would produce Codex Vaticanus. Some of these things I’m talking about are in your notes. The Catholics produced one that looks like Codex Sinaiticus. And the Catholics said it had been in the Vatican library since at least 1481. That’s the first time it was noticed among all their treasures. It was written on vellum. It had three columns. There was no ornamentation on it. And it ends at Hebrews 9:14. Once again, when you hear somebody say that these were complete Bibles—wrong! They were not. It ends in Hebrews 9:14. It excludes all the pastoral epistles, and of course the book of Revelation. It had 7,579 changes from the Textus Receptus. It also had all the apocryphal books of the Old Testament. Not as a separate section, but as though they were a part of the text all the way through. Amazing!

Two men, B. F. Westcott, who was a wonderful Greek scholar—commentaries by him are still used today—and A. J. Hort, who denied the deity of Christ, was a liberal in many areas, but was a Greek scholar. These two men got together. This story alone has been told so many different ways. I don’t know what the truth is. But it’s called The Westcott and Hort Greek Text and I was trained in it. It became the foundation of all modern English translations and still is to this present day. Now we have some evidence we didn’t have at the time. They now believe that these are two of fifty manuscripts that were ordered by Emperor Constantine, as he ordered them to be printed. And Eusebius, the great church historian, Eusebius undertook the project. We know about the project and we now believe these two manuscripts were two of the fifty that were ordered by Constantine. They needed a new Greek text. It came out of the Alexandrian school.

But let’s take a look at some of this. By the way, when Westcott and Hort put out this Greek text in 1881, not only did everybody say here is the original now, because they were the oldest manuscripts and codexes that we had ever known about. And because it was so much of the New Testament and everybody was going wild. They thought now we’re getting to the true text. And now textual criticism classes begin to develop all over both Britain and the United States, saying that the oldest manuscripts are best.

Do you understand that they didn’t have any fragments to speak of on papyrus, which is the very oldest writing material? Papyrus would have been the writing material of the original text. They didn’t have any. Most all of the ninety-some fragments on papyrus have been discovered in this century. By the way, ninety percent of their material agrees with the Received Text, not Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. So you understand they didn’t have the papyri, but they told the world these are the oldest manuscripts and this is showing us what the true text is and everybody went along with it. Why? The major translation and Bible committees and organizations around the world hooked into it lock, stock, and barrel. The hook-up with the Catholic Church was enormous. The Catholic influence in this was very powerful and that’s a well-documented fact. “These manuscripts [listen to this] differ in the gospels over 3,000 times with each other.” They sort of failed to mention that.

Now class, you can put the facts of this up to anybody’s scrutiny, I’m not afraid of that at all. This is not David Hocking giving his view. These are facts now. Which then have to be interpreted, don’t they? It is also a fact that Tishendorf made several editions of his Greek text on Sinaiticus. His eighth edition was changed in 3,369 places when compared to the seventh. Now how could you do that if you’re simply copying the Codex Sinaiticus? You know something? I didn’t live then. I never talked to Tishendorf. I don’t know anything about it other than what I read, but I’ll tell you something’s wrong.

In terms of English translations based on this codex, over 36,000 changes have been made because of this so-called evidence. And you ask me, is there any difference between the New International and King James? Yeah, there is a lot of difference. Now 36,000 changes are not that much when you’re talking hundreds of thousands of words and more, but it is quite significant, isn’t it?

The condition of these manuscripts—they are beautiful by comparison. I have seen them. When you compare them with other fragments we have that look worn, and you can hardly read the letters, and they’re torn, and they’re burned on the pages. These are like, well preserved. Now some people thought that was thrilling, but to me, that makes them highly suspicious. Before printing, can you imagine how these copies were passed around? Nobody had a copy! You didn’t have a copy of your Bible to carry into class. You were lucky to ever see one, let alone touch one or even read one. Why are these manuscripts so well preserved? They don’t look used. And if they were true texts that the early church knew existed, they would have been used.

I mentioned that the evidence of the papyri, that’s the writing material of the first three centuries, has largely been found in this century. It was not available when the Greek text of Westcott and Hort was. And the papyri evidence is older than these two manuscripts and by and large supports the readings of the Textus Receptus. Now we have a real problem. We’ve got a war. They’re claiming both Sinaiticus and Vaticanus are two of the fifty that Constantine instructed and he’s about A.D. 325—fourth century—shortly after that time.

Now class, we need to talk about a lot of things here and I don’t want to confuse you. I just want you to see some facts, first of all before we start putting this together. I don’t know how many times in Bibles you’ll see a footnote that tells you the oldest manuscripts agree. But you see, class, because it’s old it doesn’t mean it’s the best. Papyri number forty-seven is the oldest manuscript of Revelation that we have, for an example. But it is definitely not the best. As a matter of fact, there are only ten out of what should have been thirty-two leaves. So we have less than one-third of it even in the manuscript. Many, many scholars will say that the papyrus forty-seven is one of the best, but it’s not the best. Why?—because even other fragments on Revelation do not agree with it. Interesting!

You say, “Wow, how is all of this happening?” That’s a very good question. You see when the books were not assimilated together (were not in one volume) there were many other books being written and claiming to be…we had heresy running rampant! We had men denying this and that. And guess what? They could produce Scripture. It was all hand copied. You could do your own and make the changes you wanted to. And if you don’t think that happened, it happened continuously with the New Testament. That’s why it’s important for a textual critic to evaluate all the evidence, not to jump to conclusions based on one or two manuscripts. Plus the fact, that when a given heretical manuscript that had been changed was then copied, and all of the copies now are a part of the evidence. So, it may be only one variation, but it had been copied 200 times. Now I’ve got a problem that looks like 200 manuscripts agree. No. Two hundred manuscripts copied one. So you’ve got to break that problem down. Are they separate manuscripts? Or are they copies of a bad copy? Do you understand how difficult this is? This is not an easy subject.

Now, to add to our problem, let’s talk about English, which of course we know is spoken in heaven. Amen? The worst language in the world grammatically undoubtedly is the one God would choose. I doubt it seriously. But let’s talk about English. We have John Wycliffe. Today we have the Wycliffe Bible Translators in his memory, the largest missionary organization in the world by far with over 6,000 employees. Long before printing, John Wycliffe translated from Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. John Wycliffe is the one who used Jerome’s Latin Vulgate. Tyndale is the first to be printed from the Greek text and he used the one of Erasmus. William Tyndale—a tremendous story, God’s Outlaw; it is one of the most thrilling stories you’ll ever read about a man who lost his life to just get the Bible into the hands of the people. And you will get a new appreciation for the importance of your Bible—William Tyndale—that’s why his name is remembered today. There’s also a publishing house called Tyndale Publishing House.

Miles Coverdale was the first English Bible to be printed. You say, “Wait a minute. What about John Wycliffe?” Well, he translated from the Latin Vulgate, but it was never printed. Why? Printing press wasn’t discovered until 1450, long after his death. Did you follow those dates? Tyndale was a printed edition, but it was from the Greek text of Erasmus and was the New Testament. The first total (complete) Bible was the Miles Coverdale Bible in 1535, which was shortly after Tyndale.

There are a lot more Bibles, by the way. I’m just mentioning some, the Geneva Bible in 1560. Why did I put that one on here?—because it was the first to use verse and chapter divisions. That ought to explain something to you. When you’re reading your Bible, those verse and chapter divisions, they’ve been revised a lot, but they come from the Geneva Bible, an English translation. So what did they have before that? Just the text! Sometimes they are in natural breaks and sometimes they are not. But they put chapter breaks and verses in there to help the readers to locate where they were and so on and to give the general context. They tried to do them at important points that would indicate subject matter breaks. And as I look through, especially in the Old Testament, they’ve done a really good job. Really, that’s a hard job. And they’ve done a pretty good job. But sometimes, they make a mistake. Sometimes the Greek text continues, the paragraph doesn’t end until the opening verses of the next chapter. Just remember the chapter breaks and the verse divisions are not inspired. Okay?

Now we come to King James. I feel like we just have the Hallelujah Chorus played. I was asked earlier if I’ve ever seen a 1611 King James. The answer is yes. I purchased one and I have it in my possession. It’s a 1611. All of the “S”s are like “F”s. That’s the way the “S”s were written. It’s a little bit difficult to read. And it was the most important project ever undertaken for a lot of reasons. Let’s see if we can find out what they are.

First, fifty-four men did the work. Did you know that when the New American Standard Bible was done they wanted fifty-four men to be like the King James. Fifty-four men! They began work on the King James in 1607, they finished in 1610, the King James. Now they didn’t have fax machines, telephones, cars, trains or automobiles. The story is unbelievable. It’s well documented, but these men spent hours daily in prayer. Having had exposure to modern translation work, it’s usually a quick opening prayer and they were now working. I don’t know what this means to you, class, but I believe that God answers prayer. These men, when they saw differences in a manuscript would get on their knees and pray by the hour that God would direct them. There were many difficult decisions to be made, variations among the manuscripts, and they wanted to know which one was the original text.

Another thing they did which isn’t often done today like it should be. Today, portions of the Bible are sent out to individual people (this happened to me) and you do work on a given fifteen or twenty verses or a chapter or whatever. You send it back and there’s an editorial committee that makes the final decisions. It’s interesting. All fifty-four men checked and rechecked with each other less the slightest mistake would ever be made. The primary Greek text was A.D. 1550 and it’s the same Textus Receptus. It has dominated Bible translation in English for 385 years, in spite of many attempts to show its inadequacies and its archaic expressions.

One of the purposes of this text is to warn this generation of what’s happening. There’s a great undermining by Satan of the authority of the Bible and it is being done in the field of textual transmission. It’s a very serious matter.

English has not been improving in our schools; it’s been going downhill in case you didn’t know. My point is: be very careful, class, what you argue about the King James. Are there some archaic words, meaning, we no longer use them today? Yes. Does that mean they should be removed? That’s another subject. We’re now discovering that many of the archaic expressions that we were dedicated to removing, in fact express the truth of the text far greater than the new word.

An example: 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17

For the Lord Himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of an archangel, and with the trump of God. And the dead in Christ shall rise first. Then we which are alive and remain will be caught up together with them in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord.

The verse preceding that, verse 15 says,

For this we say to you by the word of the Lord, that we who are alive and remain…shall not prevent them who are asleep.

Everybody loves to say, “Well prevent, what it really means is precede.” No it doesn’t. It means prevent. Is everybody listening? Now all of a sudden we are realizing what a mistake we’ve been making correcting it. Because the intention of the writer was to show that the Rapture will not prevent the dead from ever being raised, which was the issue of the context of 1 Thessalonians. In fact the word prevent, more represents what the writer intended than changing it to the word precede.

You see, we’ve often jumped to conclusions about archaic words. It reminds me of one of my favorites, the sackbut. It’s a musical instrument mentioned in the book of Daniel. And they do everything under the sun to tell us what it is. You know what the bottom line truth is about that Hebrew word? Not even the Jewish rabbis know what it is. Nobody knows what it is. Sackbut is just as good as anybody else’s word. Nobody knows what it is. But whatever it was, it was a musical instrument in ancient Babylon.

And you know, half the time they’re making it harder on us. I see that all the time in English because I look at all the English translations before I teach any passage. And I put all of them out in the margins of my text. Everything every other translation says about any of the variations whatsoever.

You want to hear something funny? The Living Bible (that everybody laughs at) often gives the correct interpretation and it’s a paraphrase. Ken Taylor was just a dad doing this for his children. That’s how the Living Bible happened, but he was deeply versed in King James. So you see when he made his little Living Bible, what the King James said was dominating his interpretation for his children. That’s why many, many times his translation more accurately reflects what the Hebrew text is than even the modern English. It’s unbelievable! Now, you wouldn’t know that except by experience. I see it every single week.

I’m currently working in the book of Exodus and on a computer program I have sixteen translations, including the Greek Old Testament, the Septuagint. I go through every verse of that chapter and write down everybody’s variation. So when I go into the pulpit I know what every English version says about it. And you know what I see over and over again? They do not match the accuracy of the King James. The longer I do this, the more convinced I am of the importance of what we are talking about in this class. You see, what I really think is, people aren’t really studying this. They’re just parroting something they read in a magazine article about why a new translation is better than the old King James.

In Hebrews 10:10 the Lord says, “By the which will we are sanctified….” It is not we have been. It is an aorist tense. The whole argument about sanctification is an interesting one because they are all aorist tense, even though some of them look like present tense.

In John 17:17 when Jesus said, “Sanctify them through thy truth: for thy word is truth.” It looks like a present tense, continuing to do that. But it’s not, it’s aorist in Greek. In Ephesians 5:26, where it says that the washing of the water of the word has cleansed and sanctified the church. And they talk about present cleansing and present sanctification. No, it’s not. It’s the aorist tense again. Aorist means a point of time in the past and according to the Bible, the point of time in the past by which you and I are sanctified is the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ. So is there a continuing sanctification? There’s no proof of it in the Bible at all.

When it says “those who are being sanctified” it is not talking about sanctification as a process, it’s talking about people who are coming to know the Lord. As they are coming to know the Lord, they are being what? Sanctified.

In Hebrews 10:14, “By one offering He hath perfected forever them that are sanctified.” In that text it’s a present, but it’s not talking about continuing sanctification. It’s talking about those He has perfected forever are being sanctified. They are being set apart the moment they get saved—by what?—by the once-for-all sacrifice of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Let’s pray.

Thank You, Lord, again for Your word. It seems to me rather silly that we would discuss all these things and not be students of the word. That we would talk about manuscript evidence but never read it ourselves. Lord, I pray that You would give us great hunger to know Your Word. To know You in this word. We thank You, Lord. We praise You in Jesus’ name, amen.

Thank you for reviewing this lecture brought to you by Blue Letter Bible. The Lord has provided the resources, so that these materials may be used free of charge. However, the materials are subject to copyrights by the author and Blue Letter Bible. Please, do not alter, sell, or distribute this material in any way without our express permission or the permission of the author.

We invite you to visit our website at www.BlueLetterBible.org. Our site provides evangelical teaching and study tools for use in the home or the church. Our curriculum includes: classes for new believers, lay education courses, and Bible-college level content. The lectures are taught from a range of evangelical traditions.

For any questions or comments please feel free Contact Us.