When we come to the subject of context, if you were teaching a course on hermeneutics, there are pages related to context, not just this one point. Why?—because context is one of the more serious matters of hermeneutics, or interpreting the Bible.

Now class, when I say context, we need to know what we are talking about. In a simple statement that we have given as a definition, it means: observing the passages surrounding a given word, a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph, a topic, or a book. All of those are crucial. They aren’t just said to fill up the line. There’s not a one of those statements you can leave out of your understanding of context. And I’m going to now try to demonstrate that to you okay?

To rightly interpret the Bible, let’s start with a book. What do we mean by the context of a book? First, of all we mean how the book itself is organized. Who wrote it? To whom did he write it? When did he write it? And how is it outlined? Not how you’re going to outline it, but how is it outlined? How is it organized? That is crucial to understanding the passages within a book and sometimes tells you all you need to know.

Now some of them are obvious, aren’t they? Like you look at Ephesians and the first three chapters are the doctrine of the church. The last three chapters apply it. You know he begins in chapter 4:1, “therefore…” and you can pretty well get the idea. First doctrine, second principles, then practice.

Now in the book of Hebrews you have an interesting division. It doesn’t come until almost the end of the book, in chapter 10:19. Where he says, “Therefore brethren, having boldness to enter the Holiest by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way…let us therefore do this and let us therefore do that.” But see, before that we were talking about the person of Jesus Christ. Now the way it is outlined, is that “He is better than.” I have my own ideas about outlining Hebrews. But if you’re looking at Hebrews, how it’s written, you’ve got to first of all say, “Well, who is it written to?” Well, it’s written to Hebrews. Are they believers or unbelievers or both? That effects the interpretation of passages. Why?—because in the book of Hebrews we have alternating pronouns all the time; they or them, but you or us or we, and those are important in understanding. That’s all related to context.

So when you talk about a context, you have to talk about a book. Do some books tell you how the book is organized? Sure. The book of Proverbs does in the first seven verses. It tells how it’s organized. The Gospel of John tells you at the end of the book, chapter 20:30 and 31, “These signs are written that you may believe.” So it’s composed around the signs that Jesus did. I’ve noticed he constantly points out the signs to the people. And even when he’s in another passage, he reviews and keeps it in our minds. Why?—because that’s what John says. It’s John’s outline of the book.

When we come to Romans, everybody realizes the first eight chapters are kind of laying out all the doctrines relating to the righteousness of God. Then you come to chapter 9, 10, and 11 and he has kind of like a little parenthesis dealing with where Israel fits in. And then in chapter 12 on, “I beseech you therefore, brethren, on the basis of these mercies of God, that you present your bodies…(Rom 12:1).” So the whole last part of the book of Romans chapters 12 through 16 is practical application of these great truths. So the book itself reveals the context.

So class, if you’re going to study the Bible, you’ve got to start with a book. Now within each book, class, there are topics. Now sometimes the book itself indicates a multiple group of topics. For instance, in the book of 1 Corinthians, do you remember this phrase? “Now concerning spiritual gifts…now concerning meat offered to idols… now concerning….” There are multiple subjects in the book—topics. “Now concerning the things you wrote to me about marriage…now concerning these matters of immorality…now concerning the resurrection.”

You know, sometimes when you teach 1 Corinthians you wonder how they’re all related—spiritual gifts, resurrection, immorality, drunkenness at the communion table. I mean, it’s like it doesn’t fit together. I guess it all fits under the subject of carnal believers, but there are multiple subjects and how did he deal with these? He dealt with them much like a teacher did. He said that the people wrote to him about these. So the problems in the church at Corinth are being answered by Paul in his letter according to things that were written to him about what was going on. You see? So there is an example of how topics affect the context of what you’re talking about. And that’s true in many, many books of the Bible, the topic itself.

Now you can have a topic in a given passage that has multiple examples of being used, for example, redemption. We might be teaching Ephesians where it says, “In whom we have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of sin.” Well, is there not a context in the whole Bible around redemption? That’s why the computers are so handy now, because we can look up that word and find articles from dictionaries on it as well as see its many, many usages in the Bible.

But one of the key issues is a paragraph, class. I started with book, then came to the topic and now came to a paragraph. Why are paragraphs crucial to interpreting the Bible? The answer—that’s the way it’s written.

Now sometimes I have to check with the original text to make sure the paragraphs are the same. And sometimes we’re not real sure where the paragraph divisions are, but most of the time we are. And sometimes they are indicated in English Bibles. Would you believe me if I told you that the number one problem in outlining is they didn’t pay attention to paragraphs. Would that surprise you? That the biggest difficulties pastors have in outlining is they try to impose something on the text rather than let the text say what it is saying. In other words, it’s not up to us to try and figure out what kind of good outline goes on this chapter. But rather let the chapter tell you what the outline should be.

Here’s my point. In Greek a lot more than in Hebrew, there’s a central thought in each paragraph. That’s why it’s a paragraph. Much like when you write a letter, you do the same thing. Sometimes when you change and the thought is different, you make a paragraph. You indent it and you have a new paragraph. Well that’s the way it is in Greek.

So class, if I gave you a chapter to make a sermon on, a Bible lesson, or a teaching, whatever and in the chapter there were three paragraphs, how many major points would you have? Three! It’s as simple as that! Don’t make Bible study hard. Now, I didn’t tell you what the three points should be because you would have to study the paragraphs. But you understand that there’s only one central thought in a paragraph.

Now, I’m going to try to illustrate this for you so that we really get a grasp on what we’re talking about here. Turn to Ephesians chapter one and let me show you about paragraphs. Ephesians chapter one is familiar to most people who have been around the Bible for a while. So let’s take a look at it. The first paragraph is the opening two verses. So that’s just a greeting. “Grace to you and peace…” so forth.

Now would you believe that in the original text from verse three down to verse fourteen is one paragraph! And there’s only one central thought in each paragraph. Well, I don’t know if you’ve ever studied this, but there sure is a lot more than one thought there. Boy, you’ve got predestination, election, adoption, grace, redemption, forgiveness, wisdom, His will, dispensations, inheritance, the Holy Spirit’s ministry sealing you—and you tell me there’s only one thought? Yep. There’s only one thought!

Now to make it even tougher on you and I’m going to ask you to figure it out. There’s only one main verb in the whole paragraph. That’s very typical of Greek. There’s only one main verb and everything else is related to it. What do you suppose it is? Blessed! When we read in verse three, it’s not the first one, “Blessed be God and the Father….” That’s not it. It’s the next one, “Who hath blessed us with all spiritual blessings.” This whole paragraph tells us how God has blessed us with all spiritual blessings.

Now here’s something else. Within a paragraph, often there is symmetry or rhythm or meter. In other words, it’s organized for us already so that we don’t have to. So if I’m teaching this one paragraph and the one central thought is how He’s blessed us, if I don’t have any more paragraphs, then that one thought becomes the title of the message. If there were three paragraphs, it’s only one of the three major points. But if I’ve only got one paragraph, then whatever is the central point is the title of the message. So the title of the message is: “How Has God Blessed Us,” if I’m going to do a message on Ephesians 1:3-14.

Now here’s an example where I’m not imposing my outline, I’m just using what’s already there. To outline that message, I’ve got to find out within the paragraph, the context. How is it organized? You can see that in English if you look at it carefully. In praise of His glory.” You see what we have here are three stanzas. That’s why this particular paragraph was a hymn in the early church. They sang it.

There are three stanzas. It’s in symmetrical order, it’s perfect. “Unto the praise”—the word praise of the glory—glory, doxa, which is where we get doxology. “Praise God from whom all blessings flow.” They call that the doxology. Logos—word. Doxa—glory. It’s a word of glory or glorifying God. Praise God. It’s a doxology. You have three doxologies. So you have three points to your sermon on how God has blessed us, if you are only using a paragraph. So you do three things in your sermon. Three points and each one focuses on the praise of the glory of His grace. Well, how do you know what all that is? Well, let’s take a look at it. Verse three says, “Blessed be God and [what?]—Father.” It’s the Father who blessed us, the Father who chose us, the Father who predestinated us, the Father who made us accepted in the “Beloved,” verse six. So the first doxology is to the Father.

Now look at verse seven, “In whom.” Now we have to say, “who is it talking about?” It’s not the Father. It’s the last words of verse six, the Beloved. Literally, “the Beloved One,” meaning Christ. The Father made us accepted in the Beloved One, namely Christ, and it’s in whom we have redemption. And it even ends with the doxology, verse twelve, “that we be to the praise of the glory who first trusted in [who?] Christ.” Doxology number one, verses four to six, is to the Father. Doxology number two, in verses seven to twelve, is to the Son, Jesus Christ our Lord. Now what do we have in verse thirteen? “You are sealed with the Holy Spirit who is the earnest of your inheritance” So the third doxology is to the Holy Spirit. So you’ve got a doxology to the triune God in Ephesians 1:3-14.

Is everybody having fun? You see you’re getting your message ready. Amen? And all we’re doing is doing what? We’re using a basic principle of interpretation called context. I haven’t done any detailed work. I haven’t really studied it a great deal. All I’m doing is looking at the context. How is this paragraph put together? Now do you understand what I’m talking about? The front of your Bible should tell you how they have marked the paragraph. If they haven’t marked it, get a Bible that does or make sure when you are studying you have one. That’s why I always have a study Bible I can mark up and you know. And I keep my preaching Bible clean. So I’m not confused by my notes in it.

Let’s go to the matter of sentence. Is there a context around the sentence? Certainly! It would be the paragraph in which the sentence is found or whatever precedes it or follows it. For example, Ephesians 1:5 says, “…predestined us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself.” Well that happens to be a clause or a phrase, within an overall sentence. In this case I have a real problem because the paragraph is only one sentence. There’s only one sentence here in Greek—not that obvious in English. But from verse three to verse fourteen is one sentence. So in this case, I would have to look at the clauses and phrases and there are lots of them. Chosen, predestinated, accepted—all these things, clauses and phrases within it—they have a context, as you look at the sentence in which they appear or the paragraph in which they are found.

Can you have a context of a given word? Sure, everything the Bible says about the word, everything your particular passage says about the word. Is it possible that the context of a given word is different than the Bible’s context of that word? Did you hear that? The context of a given word in the Bible, is it possible that what’s in that passage, telling you the meaning of that word, would be different from all the usages of that word in the Bible? Oh yeah. I’m going to give you an example.

Go to Romans 3:24. I’m not expecting you to know all of this; I just want to illustrate it enough so that you can get the general idea. That’s why we have to do a detailed study of words, when we’re studying the Bible. It’s important how they’re used and what they mean. And I’m going to get into that at our next point of interpretation. Right now it’s just context. Context refers to how things are put together.

Romans 3:24, “Being justified freely by His grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.” I want you to look at the wordfreely and tell me what it means. What does it mean to you? Without cost!

Now go to John 15:25, “But this cometh to pass that the word might be fulfilled that is written in their law, ‘They hated me without a cause.’” Guess what? The word without a cause, C—A—U—S—E, is the exact same word in Greek translated freely, in Romans 3:24.

Just for fun let’s go back to Romans 3:24 and translate it that way and see how you come out. You might be surprised, class. Here we go: “Being justified without a cause by His grace.” That makes sense too, doesn’t it? There was no cause in us that caused God to redeem us. You see here’s an example where you’re going to have to make a decision. Does it mean without cost? C—O—S—T as it sounds in English? Or does it mean without a cause? Meaning that there is no cause in us as to why we should be redeemed? Actually the word grace there could emphasize the latter, without a cause. Because grace gives us what we don’t deserve. But it could also emphasize cost because of the word redemption, which is the word for the payment of a price. Does everybody follow me? You say, “what’s the right answer?” I’m not going to give it to you. If you’re interested you’ll have to study it. And I don’t know that there is a right answer. What I’m trying to say is that you see there is a context around a given word, not only what is said in your passage, but how it is used in different passages in the Bible. Everybody clear on that now? Okay.

Before you leave the word context, I want you to write something in your notes. There are two kinds of words that determine context: one, adverb and two, conjunction. I always begin, like when I make my notes and I’m scratching notes out, always put the conjunctions and adverbs, one of the first things you do is put them out in the left-hand margin. Just put them out there, one after another. That way, while you’re studying, you’ll always see the connection. The conjunction might be and or but. These have become very important. Ephesians 2:1-3 tells us how “we are dead in trespasses and sins, walked according the course of this world, were by nature the children of wrath, BUT God, who is rich in mercy…” tremendous contrast there. So it determines the context of the passage, the conjunction. If it says therefore, you want to find out what it’s there for, right?

Let me give you one [an example] over in 1 Peter 4 to show you how important it is. This is related to spiritual gifts. I believe that hospitality is a spiritual gift. People always ask me, “Where did you get that in the Bible?” 1 Peter 4, it’s easy, provided you are a good student interpreting the word based on what it says. I’ll tell you why. Look please at chapter 4:9. “Use hospitality one to another without grudging, as every man has received [it’s not the gift, it’s just a gift] even so, minister the same one to another as good stewards of the manifold grace of God.” Now, what’s the adverb, class, or the conjunction? Which is it?—as. When we look that up, we find out it’s cathos, which means “just as,” which means “equal to.” In other words, hospitality has to be a spiritual gift. There’s no choice in the matter. Amen? Now, it may not appear on people’s spiritual gifts list, but it’s on God’s list in 1 Peter 4:9 and 10.

You see? That isn’t my interpretation. I’m required to do that because of one simple thing, an adverb that showed the context that showed hospitality is a spiritual gift in the context of those two verses. Okay, everybody all right now? Do you understand a little bit of what I’m saying?

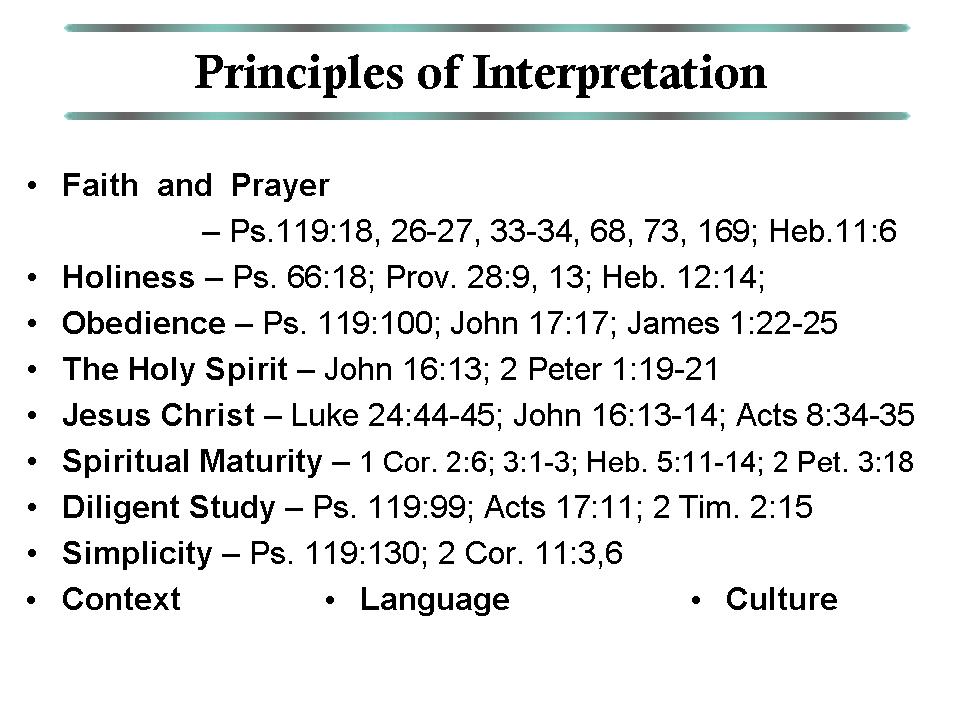

Let’s come to number ten, Language. Can we express the thoughts of God without words? No, we can’t. We can’t express our own thoughts without words, try as we may. The hardest work in interpreting the Bible is language. It takes the longest time. That’s why a lot of people skip it. You’re going to stay loyal to the study of God’s Word. Now this takes hard work. It takes time and most of the time of ever studying the Bible it’s all in this field called language.

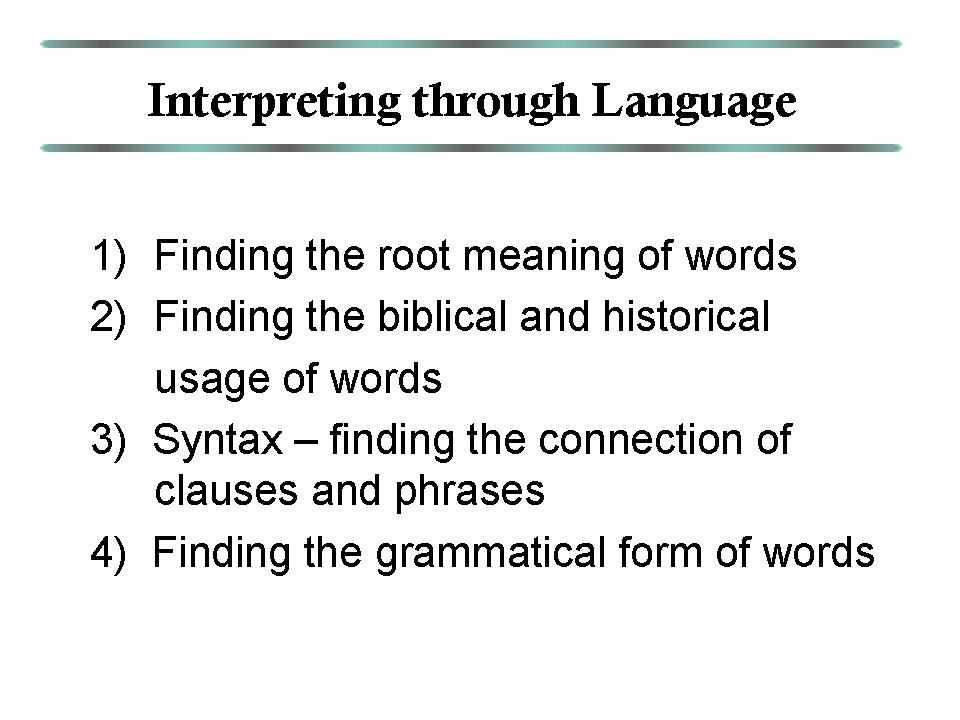

Let’s look at the paragraph I’ve given you and I’ll break it down for you. This principle of interpretation, language: finding the root meaning of a given word, noting its biblical and historical usage, understanding how the various clauses and phrases are connected together in a given passage and making sure of the grammatical form of the words. Let’s break it down. Class, there are four things to study to accurately interpret the Bible as it relates to language. Four things! Number one is what we call the root meaning of the word, which means in terms of human history, the original meaning is the root meaning of the word.

Whether you are using a computer or book, if you open a lexicon, not a concordance, you find your word in either Hebrew or Greek spelled out in English letters if you don’t know the language to just follow it. And you see a little paragraph which is very hard to understand under it. You’ll often see a numbering system. Sometimes they’re in parenthesis, sometimes not. It will say number one, number two, number three, number four. And then it will go on to another word. It will have little ditties after it. A lot of people look at that and don’t know what in the world…! Now the reason they don’t know what it’s all about is they didn’t read the introduction to the lexicon. Now if you go back and read the directions, it helps.

I remember the first time I got a Hot Wheel for my kid. Man, I couldn’t put that together. I told my wife, “there’s something wrong with it; we’ve got to take it back to the store.” I took it back to the store.

He said, “What did you do here?”

“Well I put it together.”

He said, “You read the directions?”

“Well, I…” it was just a Hot Wheel.

He said, “Next time read the directions. It explains it to you step by step.”

I don’t like doing that. I want to just do it. Just get it done. You know. Is everybody with me? That’s what I’m trying to say to you is if you read the directions on the lexicon, they’ll tell you. And normally, there are very few exceptions.

Whatever is listed first under the word is the root meaning of it. For instance, there is a spiritual gift of ruling, Romans 12:8. Some say it is leadership. That it means to lead rather than to rule, because there’s another word for rule. And they may be right. But in order to really understand it, we go back and look at the original root meaning. The Greek word is proïstemi. It’s a compound word. Histemi is used all the time in Greek today. It means to stand. Pro means “before,” either in terms of time or before a crowd, it means before an event happens or in front of people. So, to stand before in this context means to stand in front of people. So the gift of leadership is a correct one if you mean a people person, who is motivating people. He’s not task oriented, he’s people oriented. Now I learned all of that by just going to a root word. That’s all I did. So going to the root word is very, very important.

It will also show you the relationship of lots of words. Let’s take A–G. Alpha Gamma, A–G. Did you know those two little letters, if you start with them you can see scores of Greek words off of that—all of our words of purity, holiness, chastity, all of them. They are all off of that. And there’s dozens of forms of that word all off of that little root. I’m trying to say, root meanings are crucial.

Now, you say, “I don’t know Greek. What am I going to do? I want to study my Bible.” Then buy Spiros Zodhiates. It’s a two-volume set, New Testament and its concordance. He tells you what the root meanings of those words are. [You can also use the Blue Letter Bible search tools.]

Usage: root meaning first. The second thing is usage. Now class, there are two things that you’ve got to study in terms of usage to understand your Bible. One is biblical usage; for that you use a concordance. How many times is the word used? Where is it used in the Bible? Look them up! Most words are used less than fifty times, so most words you can look up. Now that’s biblical usage.

But you also have historical usage. How is it used in history? For example, in Ephesians 1:14 where we were a moment ago, the Holy Spirit is called the “earnest of our inheritance.” But you know I got to thinking about down payment. It does not mean you’ve got the inheritance. In fact, if you don’t make the payments, you don’t get it. Sounds to me like a little legalism in that. But if you go back to the historical usage of the word ararbon, you realize that what it meant at the time of Christ it still means today. It’s kind of interesting. It refers to the engagement ring. I kind of like that because one day there’s going to be a marriage to our bride groom, Jesus. The engagement ring is the Holy Spirit, that’s been given to us. Isn’t that neat? What a different idea comes on that text, all because you looked up the usage of the word. Okay.

Number three. We have first root meaning, then usage. Number three is what we call syntax. S-Y-N-T-A-X. Syntax means how clauses and phrases are connected together. And normally you’re right back to what we said under context. You’re back to conjunctions and adverbs. How important is it? Let me show you.

Titus 2:13. “Looking for that blessed hope and the glorious appearing of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.“ Is syntax important? Oh yes. Because one of the rules of syntax is that when you have two nouns connected by and, and the definite article the, is in front of the first one but not the second one, it connects equals. Is that a rule? Well, it’s used 256 times in the New Testament with no exceptions. That’s a rule. What does that mean in Titus 2:13—“Looking for the blessed hope and the glorious appearing of the great God [great an adjective, God the noun— the great God] and Savior Jesus Christ.” It means God and Savior are connected as being equals. In other words, Jesus is called God, the great God in Titus 2:13. Everybody following me? That is the result of syntax. Seeing how phrases and words and clauses are connected together and the grammatical laws that effect that. Okay? This was just an illustration, but there are many of these.

Number four when you’re looking up language and this is what takes time in studying the Bible, finding out the root meanings of words, finding out how they’re used both in the Bible and in history, and finding out syntax. But number four is the grammatical form of the word—grammatical form of the word. I can’t begin to tell you how many mistakes are made on this. It’s like the number one area where mistakes are made.

What do we mean by grammatical form? One, what person is it? That’s the very first thing you’ve got to ask. The grammatical form tells you. Is it first person? Is it second person? Is it third person? You can’t interpret the passage unless you know that. Number two, is it singular or plural? The grammatical form tells you. Is he talking to one person, or is he talking to two or more people? Is it he? Or is it them? Is it thee or ye? Is it I or us? That’s very important. Do you know that most of the warning passages in Hebrew could be solved if you just looked at the change in the pronouns and the grammatical forms of the word? When he said, “It’s impossible for those who were once enlightened, and have tasted the heavenly gift and been partakers of the Holy Ghost, and have fallen away to renew them again to repentance” (cf. Hebrews 6:4). “But, beloved, we are persuaded better things of you, things that accompany salvation.” So the “them” and the “you” are not the same. So the “they” of the warning passage are unbelievers. Your problem is solved. Is everybody following me?

You see, we get into so much trouble, so many arguments over interpreting God’s Word. Why? Because we didn’t see the grammatical form of the word, as to whether something is in aorist tense or not, meaning a moment in time in the past or whether it’s a present tense, meaning it continues. Do you know that every time God tells you how to love, every time He tells you, and illustrates it, He always illustrates it with the aorist tense? You say, “What are you talking about?”

“By this will all men know that you are My disciples, if you have love for one another even as I have loved you.” Did you know it never says, “Love one another as I have been loving you, or as I am now loving you?” Does Jesus now love us, continue to love us? Of course! But that’s not the point. The point is it’s always referring to His cross, the moment that He loved us is when He died. That’s how it’s described in passage after passage in the New Testament. So the major example to all of us in how to love each other is the cross. How did I learn that?—because I heard it in a sermon? No, because I saw the aorist tense used every time. There was no other example.

Here’s another one. “I have been crucified with Christ” (Galatians 2:20). And I heard a sermon the other day on the radio. I won’t mention who, but a guy was telling how we ought to crucify ourselves. You wouldn’t teach that stuff if you had read the grammatical forms of the words. And he used the very text I’m talking about. It says,

I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life that I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me. I do not frustrate the grace of God, for if righteousness comes through the law, then Christ is dead in vain. (Galatians 2:20-21)

When I go back to “I am crucified with Christ,” I notice in the Greek, the grammatical form of the verb is perfect tense. Perfect you usually indicate by an auxiliary verb, like have or has or had. I have been, because it’s passive voice also. I have been crucified, means it happened in the past and it has present, finished results. We don’t crucify ourselves, in Christ we already have been. You were nailed to the cross. It’s not God’s fault you don’t believe it. We’re to walk by faith not by sight. You don’t go out and do that job; it’s already been done for you. What a glorious truth!

It’s almost like the difference between teaching works and teaching grace, you know. All because a guy failed to look up the grammatical form of the word and taught it was present tense. Which he said on the radio—which it is not, it is perfect—and you lead the body of Christ astray. So don’t tell me this isn’t important. You can’t accurately interpret God’s word without looking carefully at language. It’s very important: root meanings, usage, syntax, grammatical form. What person is it? Is it singular or plural? What tense is it?—tense means time, class. Was it past, present, or future?

On my way in one of you asked me about the passage in 1 John where it says, “Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, if they don’t believe that they’re an anti-Christ” (cf. 1 John 4:3). And he [the student] said, “‘is coming in the flesh’ doesn’t that mean the future?” No, it is not the future tense. If it was it would be translated, “he shall come” or “shall be coming.” But it is not.

So again, we come back to a fundamental issue. What is the grammatical form of the word? It’s crucial to understanding. You not only have tense and time, you have another thing to add to your list and that’s what case is it?

Now, case controls the following words: nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and participles—nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and participles. What do we mean by case? Well, we have what’s called the nominative case. That means subject, the subject of a sentence. It can be a predicate nominative, which always follows the verb to be. And that can be in the predicate, looks like an object but it really isn’t. It’s the subject, nominative. We have also what is called the genitive case. In English, it basically means possession. This is a book of mine, meaning, my book. I possess it. Okay.

We have also dative case. Dative refers to the sphere in which something operates. I am in Christ. Dative. I’ve been baptized in, with or by the Holy Spirit. Meaning the sphere in which this occurs is the Holy Spirit. If I’ve been baptized in water, it means the sphere in which it happens is water. We have the accusative case. Which means, the direct object. And we have what’s called the vocative case. Which means a direct address, “O man of God, flee these things”—that’s vocative case. Okay. So, what case it is becomes important. It may interpret the whole passage for you. It may make all the difference in the world.

For instance, did you know that the case of the words answers the contradiction that people bring up in the book of Acts? In Acts 9:7, we have a statement about Paul hearing a voice, but seeing nothing. And then in Acts 22:9 they see something and don’t hear anything. But the difference between the two passages: in one passage it sounds like they heard something, the other passage it says they didn’t hear it. And people say, “Ah ha, direct contradiction!” No. If you go to the Greek grammar, the case is different that follows the word, hear. One means that they heard a sound but couldn’t distinguish the words. And another means they heard the sound and distinguished the words. So you see it depends on what case is used to determine what is meant by that grammatical form.

In other words class, I’m not trying to bore you to death. I’m trying to tell you it’s not a simple matter to interpret God’s word. It takes hard work and it takes time. And especially when you get to the subject of language, you’ve got a lot of things to look up.

Now let me give you an illustration how extra-biblical sources can also help, like archaeology or whatever. There’s a Greek word translated in the New Testament many times in the Gospels, called a multitude. Also in the Acts, “All the multitude heard Him.” What does a multitude sound like to you and me? It sounds like a lot of people, doesn’t it? If you translate that Greek word into Hebrew, it’s a word still used today. It just means the people who were there. We now believe that is a “Hebraism.” That is, it was a Hebrew word because the Lord and His disciples spoke Hebrew, we now know. It is not Aramaic. They may have been familiar with Aramaic, but they spoke Hebrew.

Now the interesting thing is that if you do what we do a lot in English, we transliterate a word. A “hypochondriac” is Greek. A schizophrenic is Greek. Sometimes we don’t bother to translate, we just say it. The word baptized is Greek. We never translated it. We just set it into English, baptizo—baptize. The same thing was done to that word, multitude. So it’s really not referring to a multitude at all. It’s just referring to the people who were there. Boy, is that an eye opener! But it solves a lot of problems also, if you see it that way.

The point I’m making is that we need to take the time to study God’s word if we’re going to interpret it. Study is the key to rightly dividing the word of truth. God said so in 2 Timothy 2:15.

What kind of books do you use to find the historical usage? Sometimes many books tell you that. For an example, Zodhiates tries to trace that word and show you some backgrounds. Sometimes there are books that are word studies. Sometimes they deal with cultural background. Sometimes they are books in Jewish circles. There are a lot of different sources for them. But you can also go to books that are like, in its simplest form, like a Vine’s Expository Dictionary. But that’s a simple attempt.

I have a little book by Herschel Hobbs, who was a Southern Baptist preacher but also an archaeologist. He has a little book rarely known called Preaching from the Papyri. It’s absolutely fantastic. It’s just great. It’s one of those books. It dealt with the usage of Greek words in the new papyri fragments that we found in the twentieth century and it adds new light to a lot of the meaning of those. You see? So all those things are helpful, they will help you understand the Bible. So will Jesus and the Holy Spirit!

Okay class, you’re dismissed!

Thank you for reviewing this lecture brought to you by Blue Letter Bible. The Lord has provided the resources, so that these materials may be used free of charge. However, the materials are subject to copyrights by the author and Blue Letter Bible. Please, do not alter, sell, or distribute this material in any way without our express permission or the permission of the author.

We invite you to visit our website at www.BlueLetterBible.org. Our site provides evangelical teaching and study tools for use in the home or the church. Our curriculum includes: classes for new believers, lay education courses, and Bible-college level content. The lectures are taught from a range of evangelical traditions.

For any questions or comments please feel free Contact Us.