Symbolic language. It is a difficult area but the simple definition doesn’t seem to be too difficult. It means: “Making a literal fact or truth more graphic or visual.” I don’t know how you were raised; some of us are raised without being exposed to this kind of conversation.

In Jewish homes, Jewish people like to illustrate what they say to give you the chance to think about it and come to a conclusion rather than point-blank say it to you. Now if you grew up in an accounting, engineering, mathematical, computerized home, they probably just wanted you to say what you want to say. I mean, some people are like this. I don’t know how you grew up, but understand that this Book is bathed in Jewish culture, Old and New. And so stories or telling a story to get across a point is very Jewish. So before you wonder why they don’t just say it, well because they want you to exercise a little discipline in thinking it through and making sure you understand.

So sometimes in symbolic language you get kind of overwhelmed with all this and you wonder: “Wait a minute, what’s going on here?” And it’s almost like you think if you were raised in the other environment that they’re complicating it. And I have been interested to notice the commentaries I have, especially on the parables you know like in the Gospels, if the guy is of the kind that I was speaking about where he grew up with: “Just the facts, man, just the facts. Just tell me straight what it is you are trying to say.” If he’s grown up that way, he is always ignoring the significance of the symbolism and he’s trying to get to the central truth. Do you understand me?

In other words, you’ll find preachers doing that. “Now there’s really only one thing being said here and here’s what it is.” Well, maybe. But maybe we ought to think about it just a bit more. So understand it’s very Jewish to take our time, especially with great moral truths. We want to illustrate it. And practically all the teaching of Jesus—one reason I know He’s a Jewish rabbi, no wonder people called Him rabbi all the time—because He taught that way, with stories.

Now when Jews tell stories, they love stories that relate to your life—what it’s like to live—common stories. Today they would say something like: “You’ve got to put water in a radiator, brother, or you’re going to get overheated.” You know, and so you’ve got to think about what they just said as to what it means. Okay. And some of the times you get the point. It’s their way of telling you there’s something wrong here, but they have a story to kind of illustrate it. Okay.

Now that’s throughout the Bible and we need to appreciate that. A lot of people who were liberal in theology, not paying attention to symbolic language, have come to conclusions about passages that are not true at all. For example in the book of Revelation alone, how in the world could anybody understand that who didn’t break down symbolic language? I’ll never know. When he (John) says something is like something, or as something, he doesn’t mean it is that. The liberal critics have used this to laugh at the Bible.

Or here is another one: “Ye are the salt of the earth” (Matthew 5:13). The other day I heard a guy on the radio explaining how we really are salt. He could prove why Lot’s wife turned into a pillar of it. But you see he was sincere, but he was sincerely wrong. Why? Because he didn’t see it was a metaphor. Now there is a point about salt that is being applied in the passage, but he’s not saying you are salt any more than saying you are a city set on a hill. But you and I both know if you’ve been around the church long enough, you’ve heard a lot of this stuff. And it gets a little mind boggling and you sometimes wonder: how did he get that?

Usually when something is quite simple and you have to ask, how did he get that? He probably didn’t get it. See, if you know something about the passage that no one else has ever figured out, there’s a chance that you might be wrong. Everybody understand that? All you’re doing, class, is making a literal fact or truth more graphic, more visual. Jewish people raised in that culture, that’s easy for them. It really is. And if you grew up in a family, as I did, that not only had a Jewish flavor to it but told stories, you learned by stories. I did it to my kids and I’m doing it to my grandkids. And I’ve demonstrated this before, but when you’re telling the story of Daniel and the lion’s den, you’ve got to make that kid understand. So you say, “He (Daniel) got in there with a lion. Do you know what a lion is like?”

“What!”

“ROAR”

And boy, they don’t ever forget that story again when they read it! You need the Lord when you’re in a lion’s den. See? You get the point, right? We’re going to make it more graphic. We’re going to make it more visual. It’s symbolic language.

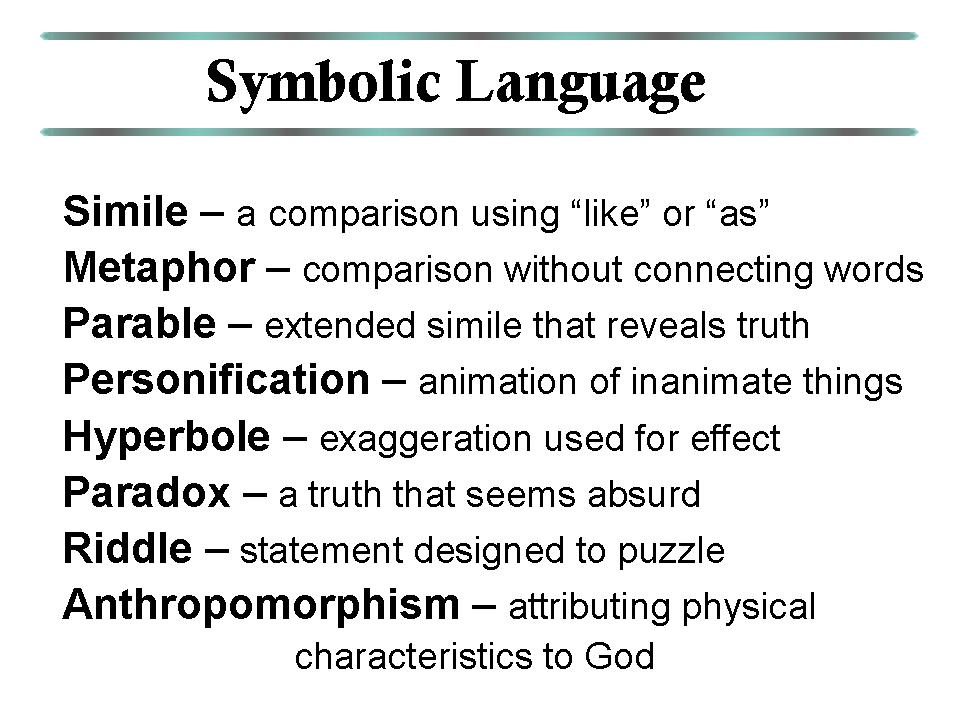

Now I have listed for you eight examples of symbolic language, but there’s a lot more. Some of them are more technical and more isolated. These are kind of what we call the eight biggies, you know, of symbolic language. And I do want you to know them.

Now one of the most frequent symbolisms in terms of the language of the New Testament is a simile. The reason that it’s important to understand a simile is because we all know about parables, but a parable is simply an extended simile. And a simile is a very brief sentence that compares two unlike things, always with a connecting word. The key here is “such as,” “like,” or “as.” It always has a connecting word. If the connecting word is left out and the two things are unlike each other and don’t make sense—“Ye are the salt of the earth”—it’s a metaphor. All a metaphor is, is a comparison without making any connection between the two. “Ye are the light of the world.” “You are a city set on a hill.” These are metaphors and there are many of them in the Bible, many of them in the book of Revelation.

I counted up over seventy examples of similes in the book of Revelation. There are a lot of them. “He had eyes as a flame of fire.” It’s like a flame of fire. Then you have to define what you’re talking about, maybe the penetrating? Burning up the dross of your life and seeing straight through you. I don’t know what he’s saying. I have my own opinion, but do you understand, just at first glance. So I’ve got to look into it a little bit. I’ve got to study the simile a little bit. “His feet are like brass burned in a furnace” (cf. Revelation 1:15). Does that mean He has solid brass feet? No. It’s like that and so the picture of it is important.

And all of that through Revelation is critical. I believe there’s a demonic plague in chapter nine being pictured, the demons of hell itself. But they come out looking like locusts and the most unusual locusts you have ever seen in your life. They’re really strange looking locusts.

So again, all the way through God’s word you’re going to see this. What is a simile, class? It has a connecting word and it is a comparison of two things. Now, before you move off of this, let me explain a Jewish simile. Jews love to compare by contrast. Exactly the opposite of what you and I do. We try to find comparisons so we understand how this is like this. Well Jews, often in the two things they are comparing are talking about something exactly the opposite. But there’s something about both of them that’s the same.

Now let me give you an example. There’s no other way to figure out the unjust judge parable (Luke 18:1-8). Why?—because the unjust judge, who hasn’t got a moral bone in his body, happens to be compared to our Blessed Lord, who is perfectly righteous. There’s a problem, a real serious problem.

We also have a thief who robs a house in Matthew 24:42-44, representing the coming of Christ. So you see, it’s a tactic of Jewish symbolic language, poetic to take contrasts. Think of how often that appears in the Proverbs. What are they contrasting? Usually it is the way of a fool with the way of the wise; the way of the righteous with the way of the wicked. And sometimes they’re two parallel statements and you think to yourself: “What is the point here?” And we Americanized [minds] think: “Oh, the point is to show the contrast between the two.” And the answer may be that, but often it is not. No, it’s to show what is similar in the two. So the Jews like to make it more graphic or visual by making it a contrast. But there’s something about the contrast that makes the two things exactly the same. And figuring that out is not always easy. That’s why Proverbs is such a hard book to figure out sometimes.

Similes are throughout the Scripture. And if you’re Jewish, you appreciate it. If you’re not Jewish and you haven’t been exposed to that kind of thinking, it’s a struggle. In fact, you find yourself trying to interpret it different than what the intention is behind it. So what I’m basically trying to get you to do is to back up a little bit, take a look at symbolic language and say, “What is the point of symbolic language here?” before I start trying to figure out the interpretation. Back up, take a longer look and say: “Is this a simile? What is being compared?” before you draw a conclusion.

“The kingdom of heaven is like unto…” so we can begin to see that these extended similes—called “parables” just because they go on longer—they may be having a lot of details. For example, the one in Matthew 22 about the kingdom of heaven likened to a man given in marriage. He happens to be a king and it’s a king’s son. And he invites certain people who find they have excuses and can’t come. So then he instructs the servants to go out to the highways and byways, get in the blind, the lame, and it says, “Bring them in here that my house may be full.” A man comes in without a wedding garment. He’s thrown out. And the application is that he’s in hell! And it kind of wraps it all up and says, “Well, many are called but few are chosen.” And sometimes we jump too quickly without backing up and taking a look. The whole thing is a simile. Two unlike things are being compared. What am I to learn from all of this? And that’s the critical point.

So symbolic language is everywhere in the Bible. The parable of the ten virgins, boy there’s one! One time when I was in seminary they asked us to take certain passages and we were supposed to look up in all the commentaries and list all the views and try to explain why they came to the views they came to. This was a good practice by the way, interrogating the commentaries instead of thinking that what they’re saying is right, investigate it. Well, I had gotten assigned the ten virgins in Matthew 25 and I’m telling you, none of them agreed! How do they come up with all this stuff? It didn’t say “the kingdom of heaven is like unto the bride and the bridegroom.” It says, “The kingdom of heaven is like unto ten virgins who went out to meet the bridegroom.” And just the details of it…like who are the wise? And who are the foolish? And what’s the point of the oil? And how, what does it mean? And apparently the five who were virgins, they were supposed to be attendants at the wedding, they never got in. In fact, they go to hell also. You think, wow! You better have a lamp or carry a flashlight around with you or you’re going to go to hell, you know.

So you see all kinds of things like the parable of the talents and the parable of the pounds and how people apply it. That’s why it’s important if you’re going to trust commentaries, and there is a reason to consult them, but if you do, make sure you don’t just have one because you’re not going to see the variety of interpretation. That’s why I try to buy books that are different, you know. And it helps you also to think through things a little bit better and try to really find out what God is saying in this passage.

Now, if a parable is an extended simile, then an allegory is an extended metaphor. All an allegory is—there aren’t many of them, there is one in Galatians 4—but an allegory is an extended metaphor.

Now go to Galatians 4 and let’s just see if we can take a look at this and understand it a little bit. Now the advantage of this passage is it tells you that it’s an allegory. So I don’t have to worry about whether it is or not. It already says it is. Galatians 4:24, “…which things are allegory.” Now there are no connecting words like or as. In verse 22, “Abraham had two sons, one by a handmaid [a slave] and the other by a freewoman.” Right? Who’s the son by the handmaid? Anyone?—Ishmael. Who’s the son by the free woman?—Isaac. The name of the handmaiden?—Hagar. The name of the free woman?—Sarah.

Now watch this. “…which things are an allegory for these are the two covenants.” Excuse me! Do you know if I did not have verse 24 and following, I wouldn’t have figured that out? That’s why people have a hard time with metaphors and allegories, why they can’t figure them out. Why? Because there’s no connecting words there and you’re not sure what is what. It takes a little time. But one thing is for sure, those are two unlike things. Is there any way that when you read the story of Hagar and Ishmael that you immediately thought it represented the Old Testament law? No way! You never even saw it. But that’s what he says. He even says ”the one’s from Mount Sinai gendereth to bondage” and that’s Hagar. So Hagar is likened to Mount Sinai in Arabia. You see, the point is that if you carry a metaphor and an allegory, if you push it to what it’s actually saying that’s what you come out with. We’ve got a woman here the size of a mountain!

Now the next interesting statement is “Jerusalem, which is above, is free; that is the mother of us all.” Then he quotes a passage about: “Rejoice thou barren that barest not, break forth; for the desolate hath many more children than she which hath a husband” (Galatians 4:27). I don’t know if you’ve ever taught this passage. Wait a minute. What does the Scripture say in Galatians 4:30? “Cast out the bond woman and the son. For the son of the bond woman shall not be heir with the son of free women. So then brethren [writing to believers] we are not children of the bond woman but of the free.”

Here’s where an application in the allegory—you don’t always have this—explains the point of it. What’s the basic point of the allegory? It’s for us to understand who the true children of the promise are. They are people who have faith in the Messiah. That’s the whole point in the argument of Galatians. They are not the ones who have been circumcised. They are not the ones who are physical descendants of Israel. Because not all are of true Israel, the remnant, who are of Israel said Paul. “He who is a Jew is not simply one outwardly, but inwardly,” Romans 2 says.

So you see the whole point of this is dealing with the difference between dealing with legalism that does not lead you to Christ and faith that does. And that’s why the conclusion of Galatians 5:1 is, “Therefore, stand fast in the liberty in which Christ has made you free. And don’t be entangled again with a yoke of bondage.” He said earlier in chapter three, “Did you receive the Spirit by the hearing of faith or by the works of the law? Which is it?” So the whole argument of Galatians is an attack against the legalistic attitudes of traditional Judaism. Very fascinating! And an allegory was the crux of the argument. It’s the key. In other words, the truth is made more graphic and visual by an allegory.

Now can you imagine what trouble we would have if you pushed every detail of that? “Well, Hagar represents the carnal Philistines. And Arabia represents the carnal Canaanites. And Mount Sinai represents all the trouble they both can get into.” Is everybody following me? I’m not being facetious for facetious’ sake, I’m here to tell you that you and I both have seen a lot of that kind of preaching. This allegory tells you what the point is. So not always are all the details to be pushed to represent something. There’s an overall truth that is there and the details lead to that truth. Here fortunately, we’ve got the application; but not always is it there. So again, it’s a specific fact or truth that’s made more graphic or visual by the symbolic language.

Let’s move to a parable for a moment since that’s something that we all are going to deal with as we study God’s word and read the Gospels; although there are parables in other parts of the Bible, not just in the gospels. The word parable comes from two Greek words. The word ballo you spell in English, B-A-L-L-O. Ballo means to cast or to throw down. And the word para, a preposition meaning alongside of. So a parable is to cast something alongside of it or to throw it down alongside of it. What is being cast alongside of is a story, usually an earthly one; one that is very common to human experience. And it’s cast alongside of the spiritual truth to make the spiritual truth clearer.

When the Lord wanted you to know how valuable you are, He cast alongside of that truth that you are very valuable to God, a story of a merchant man who would give up all to just find one little jewel. Amen? What a wonderful thing to do. He searched for it. He was willing to give up everything just for that one little deal. That is beautiful teaching. It makes it graphic. It makes it visual.

When the Lord wanted you to understand that not everybody who is listening to the word is really going to apply it, He told the story of a sower who went forth to sow (cf. Luke 8:5-15). He even gave you the application so there would be no mistaking what the point of it was.

Parables are simply telling very common things in people’s lives. You know I was thinking about this as it relates to our class, listening to Pastor Chuck. And I don’t know why, it just didn’t hit me. He is a parabolic teacher. He really tells simple stories to illustrate deep truth. And it’s amazing. I guess because when you’re not thinking about it you don’t realize how much he’s doing it. But it’s just like our Lord taught. He’s constantly giving little earthly stories. He might illustrate it with his grandchild, or how he’s in a car on the freeway or whatever. And it’s interesting how many, many times he illustrates with something that’s very easily understood in our midst. And that’s parabolic teaching, just casting an earthly story alongside of a heavy-duty spiritual truth, so that people will understand it more.

I was in Central Africa many years ago trying to teach on faith. And as I was struggling to communicate how faith operates, and all of that, and having difficulty going through different languages as well, one of the old men in the village came up to me. He spoke some broken English and he said, “After what you have said, faith is the hand of the heart.” And he walked away. You know, I’ve never forgotten that. What a simple truth. Faith is the hand of the heart. Simply reaching out and accepting what God offers. Now, I spent an hour. He spent about 10 seconds. And I thought his was better than all I’d done. Faith is the hand of the heart!

I was teaching on Matthew 18 about how Jesus said, “Except ye come as a little child you cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.” And I decided to illustrate my message. So I set it up so I could tell it. But I went out in the Sunday school facility on Sunday morning early. And I sat down on the cement in a little hallway and had my back up against the wall. And in my hand I had some candy. It was wrapped. I just laid it out there. And I purposely sat over by the little toddler department. Those kids came running up. Stopped! I mean they got brakes when they want it! Kid looked at me, looked at it, grabbed it and ran! So I put some more out there. I did this for several minutes. They all did the exact same thing. Not one of them stopped there and wanted a thirty minute lecture on whether this was good for you or not. Or is that paper real or whatever. Or why is it in your hand? That little kid just walked up, looked at it, looked at me, and whoosh off he went!

Now that’s what I call a great parable. That’s a great illustration. A lot of us make it so complex. Jesus said “You’ve got to come like a little child.” And He used the word for toddlers. Isn’t it interesting? They don’t ask anything. They just grabbed it. “Well you’ve got to give me thirty-six reasons why I just make this decision.” Well, you’re not really coming like a little child. Maybe you’d better think it over. You see, you come as a little child and it’s the hand of the heart that just reaches out and takes what God’s offering.

See, so really the more we get into this, the more we see the importance of graphic, visual presentation of truth that’s in the Bible. It’s helpful. That’s what symbolic language is. And there are many, of course, parables as you know. If you want some help on this, there are books like Richard Trench, called Notes on the Parables. He also has a book called Notes on the Miracles. And if you want to see why it’s so difficult, get three commentaries and look at what they say about the parables. Watch the differences and you’ll realize why it takes some time and some thought.

Now personification is one that causes liberal critics of the Bible to laugh. It makes an inanimate object animated. It’s not an exaggeration. Well, it’s a personification, that’s all it is. This is very much like anthropomorphism. It (personification) is attributing physical characteristics to God: “the eyes of the Lord, the hand of the Lord, the arm of the Lord.” Personification can have a tree talking. There’s a great amount of this in the Bible, where an inanimate object that really is a thing, all of a sudden becomes animated. It takes on personal characteristics. And that is a simple tool. Jews love to do that. “You know those pages just leaped out at me!” Well the pages didn’t jump over to you, but we understand what you mean. See, we have them in English to get a point across, it’s to show you the point.

Hyperbole is actually a word in the Bible [in the original languages]. It appears quite a bit. Again, ballo means to cast—only huper is over or above. So in this sense it’s like a parable. A parable you cast down to an earthly illustration. Hyperbole you cast up, in other words, you exaggerate it for effect. It’s not lying. It’s to show you the point.

Paul wrote in Ephesians 3:19 about the wonderful love of Christ that “…the Holy Spirit He would strengthen you in the inner man, Christ would dwell in your hearts by faith, and you’d be rooted and grounded in love, and you may be able to comprehend with all saints what is the surpassing greatness of the love of God—passes all human understanding.” The Greek has a word hyperbole. Does that mean no one can understand anything? No. But it is so wonderful that the average human being trying to understand it, they’re not getting a hold of it because there’s a depth there. So it exaggerates for effect. It is not telling a lie. But if you take it literally, you’d say it’s lying. It’s not telling the truth. No, it’s a hyperbole.

Now sometimes hyperbole is your exaggeration for effect to get somebody to respond to you. Like the day my wife called me and told me that one of our pipes under the kitchen had broken and there was water “all over the house!” No, it was just in the kitchen, but the way she was presenting it, it was the global deluge! I had to do something. We’re talking Noah’s flood here, man. I had to get up, run home and fix this thing and all of that. And I realized it wasn’t as bad as she had created, but it definitely got my attention. See sometimes we exaggerate for effect. Some of these are not good exaggerations obviously. Why?—because they are rooted in a bad motivation. So when people say to me, especially those who are trying to attack the Bible, when they see the exaggerations, they try to make an issue out of it. The issue is motivation. What’s your motivation? Was it to make yourself look good or was your motivation to get a point across to people that couldn’t be gotten any other way? Exaggeration for effect is a very effective communication, as long as your motivation is not evil and you’re turning people away from the truth and being deceptive and manipulative, which of course the Bible’s not doing. But there’s a lot of hyperbole.

We also have paradox. And I think you know what a paradox is. It’s a truth that seems absurd at first glance. And there are quite a bit of paradoxes in the Bible. You’ll find them in the Proverbs especially, a truth that just seems absurd, but there’s a point there. And in Jewish homes they love these. They love a paradox. What’s another word for paradox, class? A riddle, yes.

A riddle is like a paradox. But what’s the difference? Well, in a paradox you’ve just got a truth that seems absurd and it’s done that way so you will really learn the truth. But the riddle is actually a statement designed to puzzle or hide the truth. Samson had a riddle and the Bible speaks about it in Judges 14. Do we use riddles? Yeah. A farmer had twenty-six sheep. One died. How many are left? Anyone?—nineteen! Twenty sick sheep. It’s a riddle. It was designed to puzzle and hide the conclusion, and takes you a little while to figure it out.

And of course, we’ve already mentioned anthropomorphism. Anthropos— man. Morphism—the nature of. It’s taking on the physical characteristics of man and applying it to God. By the way, there are many of these in Jewish writings, more than are in the Bible and it’s very common practice.

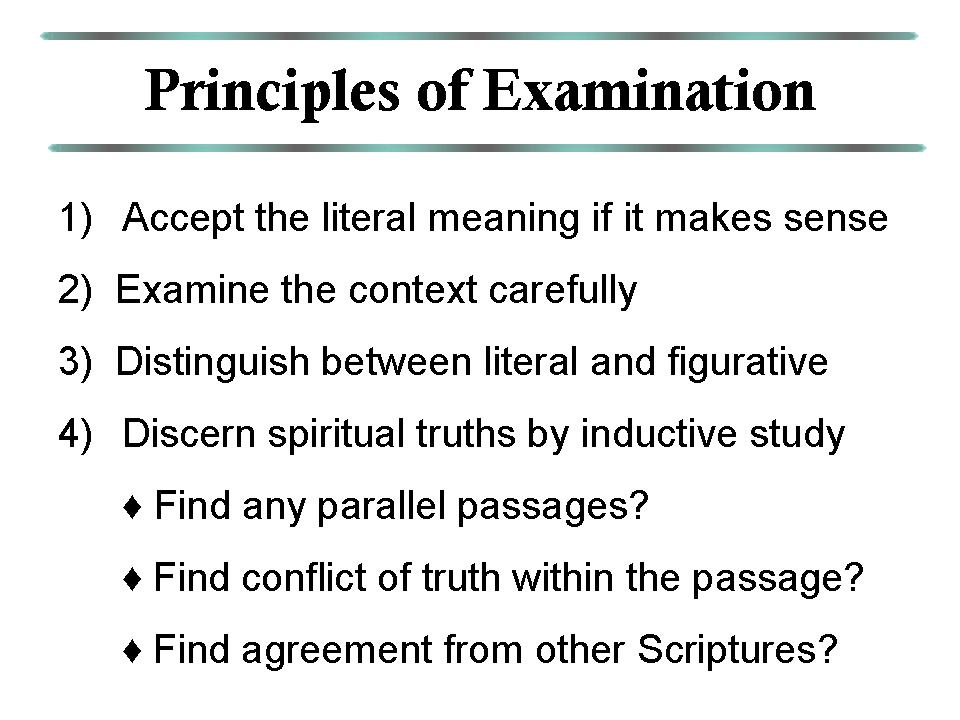

Now in giving a simple explanation here, I’ve listed for you four principles. Again, we’d take longer if this was a hermeneutics course, but just to give you a general idea. If the literal sense makes sense, then don’t seek any other sense. That’s a very common practice in the Bible. The Bible’s not trying to trick you. It’s trying to make things more understandable by the visual aid or the graphic description. So if the literal sense makes sense, then there’s not reason to seek any other sense.

When it doesn’t make sense, class listen, when something doesn’t make sense, I always consider two possibilities. One, I’m not thinking good today. I’m just not thinking good. Maybe I need to get away from it and come back to it. Or number two, it is symbolic language. And that’s the way I usually think, it’s just like automatic. Maybe it’s me. I’m the problem or maybe this is symbolic language. So, normally I find that most of the passages are easy to understand if the literal sense is there. Secondly, always examine the context carefully because what went before or after may help you understand what the meaning is of it.

By the way, that’s very true isn’t it of the parables? Think how many of them in the context had something related to it. “It’s easier for a rich man to go through the eye of a needle than into the kingdom of heaven,” was said immediately after the story of the rich young ruler who came to Christ, who had many possessions and went away sorrowful for he had all of this. So you see, there are a lot of contexts that show you what the point is.

Distinguish carefully between the literal and the figurative. That’s just a general rule. Always do that. Be careful. When Jesus sowed seed by the wayside and the fowls came and devoured it, do the fowls represent Satan? Well, we have to look at the story and it’s possible. In Luke 8:12 we know that is the point of it. “Those by the wayside are they that hear. Then cometh the devil and taketh away the word out of their hearts lest they should believe and be saved.” So now I know that the fowl of the air, which comes down and takes the seed off the wayside soil, represents the devil. Should I therefore every time I see a bird story in the Bible say that‘s the devil? No. So once again, be careful. Distinguish carefully between the literal and the figurative.

How does one do that? When you come to number four, you get your answer. Discern accurately the spiritual truth by inductive study asking three basic questions. One, are there parallel passages to consider? Well, there certainly was here in Matthew 4. When I compared Luke 8, I saw the clear teaching.

Does the truth conflict with any details of the passage? God’s word doesn’t contradict itself. And does it agree with other Scriptures? These questions can be asked and you can begin to find out whether or not the truth is there. If the Bible, class, does not tell you the meaning of something, then don’t say you know it. Do you hear that? If the Bible doesn’t tell you the meaning of something don’t say that you really know what this means. No, you don’t. You can say “I think,” or “this is my opinion,” but don’t say you know unless God’s word says what it is.

Now in the parable of the sower and the wheat and the tares, Jesus gave the interpretation—not always does He. So if there’s no interpretation given, there’s no sense of that, then don’t tell people that you know what it is. Just say, “Well you know, in my opinion it could possibly mean this on the basis of these facts.” But don’t become God in the situation unless the Lord has revealed in His word what that means.

Here is one other thing that’s not in your notes. When you see parabolic language or symbolic language, when you see it in the Bible and it’s a quotation…the Bible may even say “as it is written the barren shall do something or other or whatever”…always take the time to look up the passage from which it is quoted, because your answer may be sitting there right in front of your eyes.

1 Corinthians 1:19 tells us: “For it is said I will make foolish the wisdom of the wise and bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent. Where is the wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the disputer of this world?” If you don’t go back and look at that, you do not have any idea what the point of it is, let alone understand the meaning of it. You go back and you realize it’s a quote from the time of Hezekiah. And it’s a quote where he consulted his counselors and they gave him wrong advice instead of trusting the Lord. That’s why it’s put in that passage where it says, “The preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness, but unto us which are saved it is the power of God; For I will destroy the wisdom of the wise.” In other words, the preaching of the cross will excel all the wisdom of the world, because the wisdom of the world will think it’s foolish to preach about a man who died! But no, it becomes the power of God because of what He accomplished there.

So understanding the background from the Old Testament helps me to see why this language is seen rather symbolic, why it was put there in that passage. So when it is a quotation, be sure to always look up the passage behind the quotation. That will help you and save your neck many times in interpretation.

We have one more session of very interesting material.

Let’s pray.

Father, thank You so much for Your love and Your word, Lord. And thank You that we have a sure word that we can trust and depend on and can change our lives. Lord, help us all to be good students of this word. We thank You in Jesus’ name. Amen.

Thank you for reviewing this lecture brought to you by Blue Letter Bible. The Lord has provided the resources, so that these materials may be used free of charge. However, the materials are subject to copyrights by the author and Blue Letter Bible. Please, do not alter, sell, or distribute this material in any way without our express permission or the permission of the author.

We invite you to visit our website at www.BlueLetterBible.org. Our site provides evangelical teaching and study tools for use in the home or the church. Our curriculum includes: classes for new believers, lay education courses, and Bible-college level content. The lectures are taught from a range of evangelical traditions.

For any questions or comments please feel free Contact Us.